Accessing Disability Culture

Accessing Disability Culture is a reflection of experience, resistance to ableism, and documentation of disabled/neurodivergent/chronically ill/Deaf students at the University of Michigan. The idea for the project evolved over several years, but first sprouted during the Summer of 2022, when I was being mentored by Dr. Remi Yergeau through the Women and Gender Summer Fellowship Program. As a part of my project, I read Loud Hands: Autistic People Speaking, and was enamored as a young neurodivergent student, to see how artfully the “voice” of autistic identity was reclaimed and wielded by the authors of this work. Who better to tell our stories than ourselves? Just before this book, I had read Asperger’s Children, and continued diving into autistic history, consequently mourning the generations of medical abuse, social death, and erasure of autistic and other disabled kin ancestors. How, I began to wonder, are ableist structures within academic institutions, or any other institution, to change, when dominant narratives on disability are not dictated by the people they affect the most? My hope is that Accessing Disability Culture is a way of translating our realities as disabled students into the understanding of not only allies looking to contribute to the advancement of disability equity, but also to other disabled students searching for a disability cultural anchor at University of Michigan.

You will notice an array of positionalities, identities, and opinions in this anthology, which reflects the diverse nature of the disability community. Additionally, you will distinguish the variety of mediums - photography, installation, essay, poetry, digital design, and more. A prerequisite to inclusion in this collection was accessibility and freedom of diverse expression in the submission. Throughout each step of the process, accessibility experts in the Digital Accessible Futures lab worked alongside contributors to make pieces accessible. Additionally, in our call for submissions, we specifically focused on keeping prompts relatively open, noting our values for intersectional experiences and accessibility, but trusting in the direction of individual creators. As a result, the themes are nuanced and intertwined, depicting disabled embodiment and life, grappling with inaccessibility of the University as disabled students subjected to academic ableism, and asserting crip wisdom, joy, interdependency, and overall - disability culture. In Accessing Disability Culture, we control our own narratives. Disabled students of the University of Michigan celebrate community, acknowledge the distance between our current experiences and disability justice, and dream of an accessible future.

Sincerely,

Tess Carichner, lead editor of Accessing Disability Culture

The Unnatural Conversion of Energy (2022)

Image Description: Four black and white images depict a young man in a wheelchair. There are ghost-like apparitions around his arms and head that display movement. Although the movements are hard to see, they depict the man having a seizure.

About the Creator

Conversion disorder is a condition in which a person experiences physical and sensory problems, such as paralysis, numbness, blindness, deafness or seizures, with no underlying neurologic issues. The brain converts extreme amounts of stress into physical symptoms as a form of defense. Despite living with these seizures for ten years, I have grappled with the issue of how to creatively document my seizures. I wanted to capture the movement and brutal honesty of these events. With the help of some fellow artists, I induced a seizure while burst images were taken and later layered together.

Charlie Reynolds (he/him) is a conceptual artist who explores themes of war, gender, and disability using fibers, installations, and sculpture. During his time at the University of Michigan, Charlie hopes to expand his practice with a specific interest in weaving, hand dyeing, and quilting.

Image description: Charlie is a young white man with short brown hair. He is wearing glasses and white shirt with colorful stripes. He is looking at the camera with trees in the background.

I Bite My Tongue

“They just got the official diagnosis.”

“Really? Poor thing. How’s her mom doing?”

“She’s taking it pretty rough I think.”

“That makes sense. I remember when we found out about my youngest. I just cried in the car for hours.”

This is the conversation that I overhear during my first week at my new teacher’s aide job. The two teachers I will be working with that year are discussing a student who has recently been diagnosed as autistic, but from their somber tone and hushed voices you’d think she’d just been given a cancer diagnosis. I want to ask them why this is such a tragedy. I’ve met the student they’re talking about. When she’s happy, she hums. When she’s stressed, she flaps her hands and rocks. She likes her personal space and will make it clear to you when she doesn’t want to be touched. At this preschool, they do little write-ups for the parents about skills their children are developing; sometimes they’re about fine motor skills or language development. Will her stims and behaviors be included when they write to her mom about how she communicates? My guess is probably not. Maybe if she were communicating verbally or using her hands to form the baby sign language that they teach the students. But her stims and hums and grunts are just quirks to them. Behaviors that will be considered less and less acceptable to society the older she gets. I suddenly find myself faced with the choice to disclose my own diagnosis or keep it to myself. I decide on the latter, a decision I will continue to make time and time again over the next three years working with children.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This year I am moved to a different classroom based on some scheduling changes. I’m entering my third year of nursing school and I’m thankful to have a job that accommodates my schedule. I’m working with a new teacher named Lindsay that I don’t know very well. Despite my social anxiety, I really try to connect with her. I ask her questions and am met with one word answers. Any attempts I make to get to know her better are brushed off. Whenever we interact, I get that same bone-deep feeling of being disliked. Being a high-masking autistic person, I have developed a sixth sense for this sort of thing. Neurotypical people often can’t tell that I am autistic, especially when I’m actively masking, like I do at work. However, while they might not be able to identify that I’m neurodivergent, they can always tell that there is something a bit “off” about me. That makes them uncomfortable. It doesn’t matter that I studied their social cues like there was going to be an exam on it, and learned what I was supposed to say, how I was meant to react. So Lindsay didn’t like me, that's fine. One day she tells me she’s leaving early for a class she’s taking. I ask her what class. (I still try to make small talk with her, old habits die hard). She tells me she’s studying to be an ABA tech and suddenly a lot more things make sense.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

As someone who has worked in healthcare for five years, and is currently pursuing my Bachelor’s of Science in Nursing, I hear a lot of off-color remarks from nurses about autistic patients. I’ve begun to learn during my clinical rotation this semester that pediatric environments are certainly no exception. Pediatrics is one half of the Peds/OB semester, the semester of nursing school I have been looking forward to the most since I started. I wasn’t expecting it to remind me so much of my job at the daycare, or my time in high school for that matter. The nurse I am shadowing that day doesn’t seem thrilled to have a student, she’s even less thrilled when she gets a new patient assigned to her. “Low functioning autism,” she sighs, looking over his chart disapprovingly. “This is gonna be a long day.” I think about explaining to her that functioning labels are actually widely disliked by the autistic community (1); then I wonder if I should refer to the autistic community as my community or just leave that part out. By then, nearly a full minute has passed, which I think is probably beyond the socially acceptable time to mention something. I leave it be.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The nurse that I am shadowing the day of my next obstetrics clinical seems really sweet. She’s the primary nurse for a patient that’s in for a scheduled C-section. The patient arrives and goes to change into her hospital gown in the bathroom, while I awkwardly stand around watching the nurse make small talk with her husband.

“What does your wife do for a living?” She asks him.

“She’s an ABA tech,” he responds. “Works with autistic kids.”

“Bless her,” the nurse says. She clasps her hands together and makes a little noise. She’s acting like he told her that his wife rescues orphaned kittens and not like she uses classical conditioning to train autistic kids into acting neurotypical. His wife comes out of the bathroom and I take her vitals. I wonder what she thinks she is doing when she goes to work every day. What does she think of her autistic clients? If she knew that I was autistic would she still be as happy to have me assisting in her care? When her son is born several hours later he doesn’t cry. The nurses quickly take him to the warmer and assess him, then bring him back to mom and dad. Still, he is silent. His parents are worried. I’m a little worried too. I’ve never seen a newborn so quiet. The nurse tells us he’s completely fine. Both his lungs sound good. He’s just not very talkative.

“He’s perfect, so beautiful,” his mom says; she’s staring at his tiny face, amazed. He continues to remain completely silent, apart from a sneeze, until we take them to the recovery unit and he gets his first shots. Then, we get to hear his cry. His parents seem relieved that he can make those noises. I think about how my brother, who is also autistic, didn’t speak until he was three. Then I think about how one in thirty-six boys (2) in the U.S is diagnosed with autism, and I hope that this baby is not one of them.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Lindsay and that child’s mother clearly aren’t going into ABA work with malicious intent. I’m sure that they actually think they are doing a lot of good, helping autistic children and all that. But intent doesn’t really matter when the impact is so profound. Applied behavioral analysis or ABA is considered the “gold standard” for autism interventions. The goal, according to those who practice and promote it, is to increase behaviors that are helpful and decrease harmful behaviors. It utilizes positive reinforcement to discourage so-called problematic behaviors and encourage good ones. But who determines if a behavior is problematic? Who determines when an action is harmful or disruptive to learning? I’ll give you a hint, it’s not autistic people. At its core, ABA is centered around “correcting” behaviors that neurotypicals deem problematic. No thought is put into what these behaviors represent. It rewards autistic kids for conforming and punishes us for being different. It is centered around modifying behavior, not understanding what said behavior is trying to communicate (3).

I often wonder how much contact these people have with the autistic community outside of the children they work with. What happens when autistic children grow up and become autistic adults? ABA teaches children to mask, to stop stimming, to make eye contact and respond to social cues. It teaches us how to make ourselves palatable to neurotypical people, instead of encouraging us to continue developing our own communication skills in our own neurodivergent way. I think about these things every single time I’m accosted with an insensitive or downright offensive comment about a child with autism. Sometimes I feel like a hypocrite. I never had to go through ABA, thank goodness, but I still spend so much of my energy trying to convince neurotypical people that I am like them (even if most of the time it is pointless). I could say something but I never do. I never tell them that all those autistic children that they discuss as if there were something wrong with them are going to grow up into autistic adults who will have to unlearn all of that. I know because I’ve had to unlearn the terrible things I have been led to believe about myself and my community

I don’t know exactly why I keep quiet. I think part of it is the fear of being judged, this worry that others will think that my being autistic will somehow make me less capable of doing my job. I hold out hope that it won’t feel this way forever. After all, I used to mask all the time, not just at work or school, but even when I was hanging out with my friends or family. It had become second nature to me. Most of the time, I wasn’t even aware I was doing it. Then I got to college and I met other autistic people, became friends with them, and learned more about the community- my community. Bit by bit, I found myself unmasking. I stopped suppressing my tics and stims. I started using my fidget toys that I hadn’t touched since a classmate made fun of them in middle school.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I’m playing “police tag” with my students at work, a game that involves me chasing after half a dozen or so preschoolers and trying to catch them while they pretend to be “bad guys” running away. I’m out of breath and stop to take a quick break when I feel someone grab my hand. I look down and see Rosie holding onto me. She’s a student in one of the other classes. All I really know about her is that she’s autistic and has a difficult time socializing with her peers due to her tendency to sometimes push and hit them. She usually spends most of recess being closely surveilled by one of her teachers. “Run?” she asks, tugging on my hand a little. She spends the next hour holding my hand and running with me while we chase down the other kids. When it’s time to go back inside her teacher comes up to me and tells me that she’s never seen Rosie play with any other teacher like that. “Rosie and I just get each other,” I say, smiling. It’s not the full truth, but it’s something.

Works Cited

Functioning Labels Harm Autistic People - Autistic self advocacy network. (2021, December 9). Autistic Self Advocacy Network.

https://autisticadvocacy.org/2021/12/functioning-labels-harm-autistic-people/

Data and Statistics on Autism Spectrum Disorder | CDC. (2024, January 10). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/data.html

What We Believe - Autistic Self Advocacy Network. (n.d.). Autistic Self Advocacy Network.

https://autisticadvocacy.org/about-asan/what-we-believe/

About the Author

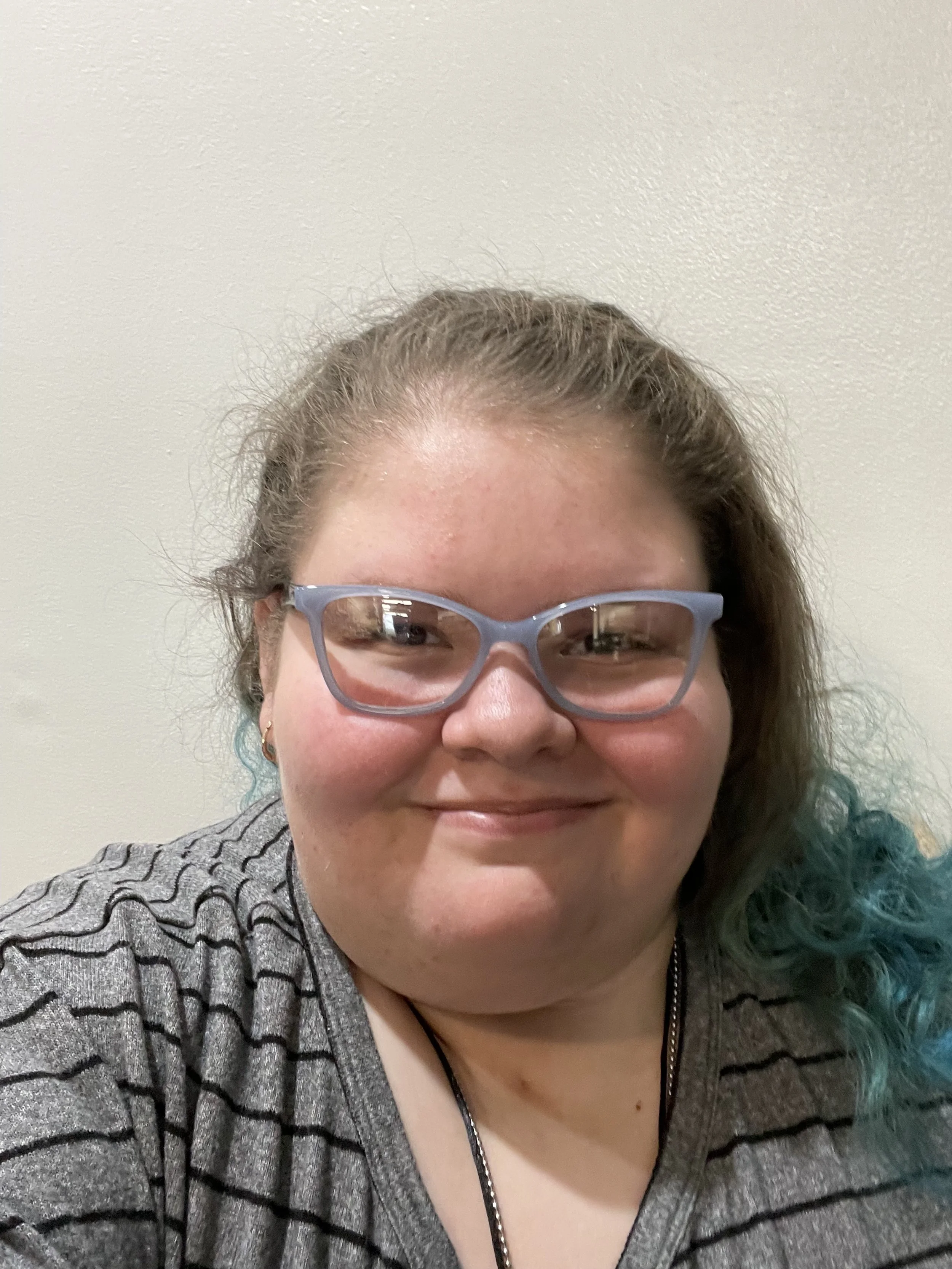

Madeline Ferris (she/her)

I'm a junior in nursing school. I'm originally from California. When I graduate I'd like to be a pediatric nurse.

Migraine (2020)

Image description: A pinkish-red brain fills the majority of the canvas, consisting of tube-like structures. Three veins wrap around and squeeze the brain while one ties the stem of the brain in a knot. There are two gunshot-like holes in the brain dripping dark red blood. A bright blue ice pack sits on top of the brain, appearing to be unhelpful. The background is a dark red-purple, with flashes of white stretching out from behind the brain.

This piece focuses on the debilitating effects of migraines and the invisibility of their nature. Though a physical disability, it is all happening inside the body, leaving room for others to dismiss or downplay it. A pinkish-red brain fills the majority of the canvas, consisting of tube-like structures. Three veins wrap around and squeeze the brain while one ties the stem of the brain in a knot. There are two gunshot-like holes in the brain dripping dark red blood. The restricting veins and gunshots are the overwhelming pain. The flashes of light are the sensitivity and loss of sight. The ice pack is the ineffectiveness of treatments. These all occur out of sight from others. A bright blue ice pack sits on top of the brain, appearing to be unhelping. The background is a dark red-purple, with flashes of white stretching out from behind the brain.

About the Creator

em laffey

I am an undergraduate and first-generation college student studying Political Arts, including painting, poetry, and photography. I recently transferred from a community college in the suburbs of Chicago. My studies revolve around social issues, specifically institutional, as I also plan to study civil rights in law school after undergrad. I also work at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender here at the university and as an art teacher back home.

Image description: em is a young white woman with long brown hair. She is wearing a black shirt with a white vest and is smiling at the camera.

Ode to Headphones

when the outside pierces the inside

car horns, shouts, bus brakes, undulating background chatter building

till annoyance becomes physical pain

my ears are folded in by my hands

my eyes are swollen in their tear-lined sockets

the vibrations that radiate from the impact of my heel on the ground are measured

with just one sound

from the conversations, the day, the peace - I am severed

my favorite gift was not very expensive

it was not trendy, then at least

it was an object and

a new way of knowing the world

over-the-ear headphones

now scratched, stickered, peeling

loved

something worn on the outside

to bring peace to

the inside

I left class one day

without them

my instructor ran after me

WAIT

what would you do without them?

some nights

they cushion my head as I drift to sleep

some evenings

they narrowly avoid water as I shower

most days

they are as essential as shoes

every day

they are a friend

a protector

About the Author

Tess Carichner (she/her) is the editor of Accessing Disability Culture, a research assistant in the Digital Accessible Futures Lab, and a junior at the University of Michigan School of Nursing. Tess' passion is in understanding ableism in healthcare spaces, especially ableism perpetuated against autistic women and gender diverse people. She hopes to pursue further education and research in relation to anti-ableist healthcare practice and curriculum. When not in class or planning her next disability justice event as the founder of Disability Justice @ Michigan, Tess can be found thrifting her outfits, listening to audiobooks, showing people pictures of her dog (Toni), and collaging with recycled books.

In Ode to Headphones (2023), Carichner reflects on a piece of technology that, while casual in presentation, actually creates sensory access in her everyday life as an autistic person. The brief interaction in which an instructor urgently recognizes a piece of "casual" tech as an assistive device is an uncommon, yet necessary example of sensory needs being validated. Lastly, Carichner reflects on the user's regard of assistive devices, as the headphones become a part of the routine, the experience, and even the user herself.

Image description: Tess is a young white person with whitish-blonde wavy hair and freckles. She is smiling at the camera and standing in front of a blurred nature-green background. Tess is wearing a blue dress and a matching blue stone choker necklace.

This is UMich

I had been waiting for this.

With the rain of confetti on my screen, I knew I was going to “Go Blue.” Ever since I was a little girl, I dreamed of attending the University of Michigan. Maybe it was because my favorite color was blue, or that my older brother had attended the school, or simply because it offers vast social and academic opportunities for students. With such a large and diverse campus, it would be accessible for me, right?

I was excited about this.

Along with my admission, I was also accepted into a living-learning community where I would connect with other members over our passions as future health professionals. Our community is dedicated to learning about health disparities, so we take additional classes together, one being focused on health and the healthcare system. The curriculum lightly touched on disability discrimination, stating the unfortunate reality that a majority of doctors would prefer to treat patients without disabilities. Additionally, a 2011 study found that those with disabilities “receive significantly fewer preventive services and have poorer health status than individuals without disabilities” (Reichard, 2011). As a result, patient outcomes are much worse for those with disabilities. That’s where we come in. As the next generation of doctors, nurses, public health officials, and more, we “Gen-Zers” will be the ones to tackle these long-established issues head-on.

While I’m only in my first year of undergrad, I already intend to major in neuroscience on the pre-med track. I have a disability called Erb-Duchenne Paralysis, or Erb’s Palsy. It’s a type of brachial plexus injury from birth. I was adopted from a rural area of China, so I don’t know any of the specific details. What I do know is that there is corrective surgery for this condition, but only within a small window of time after birth. Otherwise, there is currently no technology to repair my damaged nerves. This has motivated me to study neuroscience and become a doctor, but also to hold a goal of eventually conducting my own studies on neural growth and regeneration. I understand how the research I will conduct can positively impact the neurodivergent and disability community. I am not passionate about research to only develop treatments, as that itself can oftentimes perpetuate ableist messaging, but I want to conduct translational research that gives patients more options than “there is no cure.” Thanks to UMich’s commitment to expanding research opportunities, I was able to find a research project in my first semester investigating goals for end-of-life care for patients with Alzheimer’s and Dementia. While my current dreams to pursue an MD/Ph.D. may change, my passion for medical science keeps me excited for the future.

I also rekindled my love of music by joining the Arts Chorale, a choir on campus that includes a diverse group of individuals and majors. Singing helps me to escape my anxieties and self-consciousness. The feeling of being completely in the moment, effortlessly echoing the rhythms with an orchestra behind you, brings me indescribable joy. Just as important as medical treatments, holistic treatments can be essential to individuals living with disabilities and/or neurodivergence. Music serves as a valuable, nonpharmacological resource to boost mood, community, and self-confidence.

At UMich, I found something I had never had before, a group for disability advocacy. When I was younger, I was ashamed of being disabled. Due to my limited mobility and permanently bent elbows, I would always wear long sleeves and hoped that nobody would notice. Still, my ears were not averted to people’s snide comments and my eyes could see their second glances. With access to the internet, I see disability and neurodivergent representation, but also numerous ableist videos on social media mocking those with such identities, unfortunately outweighing the positive messaging. Due to the fear of shame, I never truly embraced my identity as a disabled person or shared my everyday struggles with anyone until I joined DAC HP (Disability Advocacy Coalition for Health Professionals). In the club, we have held discussions about our experiences living with disabilities/neurodivergence. It is here that I finally found a community that I know is safe and can relate to this aspect of my identity. We harbor respect for each other: our individual and combined experiences drive what we pursue.

Little did I know that this University required us to constantly advocate for our communities.

I did not expect this.

Ableism is everywhere. At first, it was the bathroom stalls and showers not having accessible hooks. Then it was having to return dining hall dishware on rotating trays up high. There are many accounts of students being outed for having testing accommodations by professors or taking tests in a faraway building. Numerous building layouts don’t allow easy access to elevators, and finding the specific elevator that services your floor can be exhausting. More specifically, there is also deeply rooted systemic ableism. Some colleges, such as the School of Nursing and LSA, require individuals to consent to potentially waiving their need for accommodations according to the University’s Technical Standards. These ableist designs require change, both in policy and in the attitude of faculty and stakeholders. While I’m not naive to the fact that ableism is difficult to eliminate, I never expected it to be entrenched in both day-to-day and professional life.

We can change this.

I cannot express my appreciation for the SSD (Services for Students with Disabilities) enough. They help to provide specific and unique accommodations for students. Their purpose and worth cannot be overstated. I have received accommodations in the form of step stools for my reach limitations in the lab and access to an ebook database due to the weight restriction on my back. Because of these resources, I can start my education in the medical sciences and complete my necessary labs.

That being said, these ableist issues persist at the university. It’s organizations such as DAC HP, Disability Justice at Michigan (DJAM), Medical Students for Disability Health and Advocacy (MSDHA), Disability Culture @ UM, Autism Spectrum Coalition, D/deaf and hard-of-hearing Wolverines, Council for Disability Concerns, Society of Disabled and Neurodiverse Students, and more advocacy or support groups that work tirelessly to get these problems addressed and create safe spaces. By calling out these problems, and creating solutions, we can collectively combat ableism and expand access in areas big or small. It is oftentimes the day-to-day issues that consistently negatively affect our communities. Even in my first semester, I created an SBAR(Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation) advocating for the bathroom hooks to be lowered in my dorm for my healthcare class. Whether my request is fulfilled or not, I know it is essential that I use my position as a student and my voice as an advocate to keep pressuring the University to live up to its claim of inclusivity for all students.

An ideal future would be for disabled/neurodivergent/chronically ill students to be supported by able-bodied individuals just as I have found that these communities have been supportive of me. In these communities, we recognize that we don’t need to pity or idolize each other. We are people motivated by our disabilities, but not defined by them. Our disabilities or neurodivergence is a part of who we are, but not who we are. By having a diverse network of allies, our requests may be listened to and revolutionize the current culture at UMich. This, we can achieve together.

Works Cited

Reichard, A., Stolzle, H., & Fox, M. H. (2011). Health disparities among adults with physical

disabilities or cognitive limitations compared to individuals with no disabilities in the

United States. Disability and health journal, 4(2), 59-67.

About the Author

Anna Xianyu Bochenek (she/her)

I am a first-year undergraduate student in the college of LSA. I was born in Donyang, China, and grew up in Rochester Hills, Michigan. I plan to major in neuroscience on a pre-med track while continuing to be an advocate for disability justice. My hobbies include singing, playing the ukulele, connecting with my Chinese heritage, and spending time with my Shih Tzu dog named Holly!

Image description: Anna is a young Asian woman with mid-length black hair and dark brown eyes. She is wearing a black dress and a gold butterfly necklace. She is smiling at the camera with her hand resting against her chin.

Labels.

I feel like I should start with an introduction, so you know that I am a real, true, existing person, and not some straw person to further an agenda.

Hello. My name is Atlas Etienne. I am 23 years old. My pronouns are they/them. I’m a junior at the University of Michigan. I am also disabled, neurodivergent, queer, fat, a non-traditional student, the child of an immigrant, and many, many other things. I’m also a musician, a writer, an amateur activist, a video game enthusiast, a sibling, my parents’ child, and more. What do these labels tell you about me? Well, some of those labels tell you what to call me, but they dramatically oversimplify my overall experience. Some of these things are obvious to the people who walk past me every day on campus. Some of these things surprise my friends.

Do these labels tell you that much?

No. So let’s get onto the story, about labels that can help you understand who I am. I was born at the tender age of— Oh, we’re not doing that? Alright. Let’s talk about my disabilities. I have seen people accuse others of faking their disabilities... because they have more than one. Some neurotypical and/or able-bodied people don’t always understand that disabilities come in bulk; some show up at the same time, and others come as a result of a pre-existing condition. For example, I’m autistic with ADHD. These are neurodevelopmental, so I was born with both. I don’t know if my generalized anxiety disorder and germaphobia came with those two, or if they showed up later, like the depressive episodes, complex trauma, and chronic pain. Surprise! They had a buy-two-get-17-free sale when I was shopping, and I took full advantage of the bargain. That was a joke, in case you couldn’t tell.

I was labeled “gifted” when I was five, which is funny, because I could read, write, and do math at an early third grade level, but I wasn’t solid on tying my shoes, and I had to be taught how to bounce a ball. Anyone around my age can tell you that if your first “different” label was “gifted,” it meant one thing for sure– nobody was going to diagnose any of your ongoing issues until you figured out what they were.

Looking back, I can see clear evidence of Autism and ADHD. I had texture sensitivities. I could walk past a room and hear when an electronic was on even if it was muted. I had no clue how to socialize. I was the most gullible person to ever exist. This, of course, led to a lot of problems. Being desperate for friends meant I ended up with some very terrible friendships, including an abusive friendship that left me with chronic pain and a lot of issues.

The internet was, for me, what it was for many other disabled or neurodivergent kids: a refuge where you could make friends by interest instead of by appearance and region. It was a resource I got really good at using for figuring out the problems my doctor wouldn’t listen to, at the time. It was where I learned about myself, and found the information I needed to understand myself. The internet helped me gain some confidence, even though I still struggle with keeping that confidence. Once I had answers, the internet helped me find resources to work on what my ADHD medication wouldn’t fix, accept the fact that I’m autistic, and find some stretches for my chronic pain. I joined groups, communities, and other similar spaces specific to my disabilities, and got to interact with other people who had similar identities and struggles. My labels helped me find those communities.

The internet helped me prepare to transfer to the University of Michigan. I’m nearing the end of my first semester at the university, and I wish I could say that it’s been perfect, but nothing ever is. I have found clubs for neurodivergent students, and I attend meetings for one of them every week, which has done a lot for me. It’s a place where I feel accepted. I can stim freely. Plus, since most of us have other disabilities as well, I found acceptance for more than one of my issues in that space. My teachers are understanding of my differences. At the same time, orientation was a nightmare for me, and I still occasionally feel judged by my classmates. But I have hope because I feel that I can help people understand my experiences.

I hope that the student organization I attend (and others like it) will help other neurodivergent students to feel more accepted and understood on campus. I hope our advocacy and activism, however big or small, will lead to better spaces and resources on campus for neurodivergent students and staff. I hope my in-depth review of my orientation experience, of being left behind by two separate orientation groups because I walk slowly and have to take breaks, will help future chronically ill incoming students. I would like to believe that one voice can make a difference, but even if it can’t, I know I’m not the only one. I’m not the only person who notices inaccessibility. I do believe that the University of Michigan is doing the best it can with its current knowledge and resources, but the people in charge need to know what’s going on for them to have any chance of fixing it.

To end on a more positive note, let me give you a recap of the last club meeting I attended, so you can understand what autistic student culture means to me.

The room that was reserved didn’t have tables, but floor time is good for autistic people anyway. I said, “Floor Time!”1 Others repeated me. A few meetings ago, I brought a bulk pack of Boink fidgets and a bulk pack of snap-and-click fidgets to the club meeting, and have had the remainder in my backpack ever since. I pulled them out again. Most of the relatively-small group played a board game, while I and two others sat around flinging Boink fidgets across the room and talked about life, our interests, and whatever highlights or complaints we had from class that week. When the first board game was done, some of the players swapped out. Now there were four of us who chose not to play, sitting around talking about whatever came to mind.

We stim freely. We infodump without embarrassment. We have rules to avoid certain topics, but otherwise, we’re free to talk about almost anything. And we happily show up as often as we can, because it’s fun to be in a space with people who understand you. So when I think about disability culture, whether I think about neurodiversity, mental illness, physical ability, or any similar topic, I guess what I think about most is the feeling of being understood. I’ve only ever felt that at home before. And that’s what my labels mean to me. My labels represent identities, many of which aren’t well-understood by other people. And that’s okay, because my voice gives me the power to help others understand. I use my labels to find community, but I also use them to build bridges and create understanding.

People have often asked me why I cling to my labels. I suppose those of us who are chronically online would like to consider them closer to “tags” on a post. I have these labels so that the right people can find me, and so I can find the right people and resources for me.

This is a bit of community knowledge that is widely discussed amongst Autistic people, but can be hard to find information on. Here’s one essay: https://thinkingautismguide.com/2016/04/when-chairs-are-enemy.html

About the Author

Atlas Etienne (they/them) is a Junior at the University of Michigan. They were born and raised in Miami, Florida, and are passionate about music, writing, and social justice. When they're not dedicating all their waking hours to schoolwork, they enjoy spending time with their friends, family, and their partner, Ryn.

Image description: Atlas is a young light-skinned feminine person with mid-length hair that is brown at the top and blue near the ends. They are wearing glasses and a gray shirt with black stripes. They are smiling at the camera.

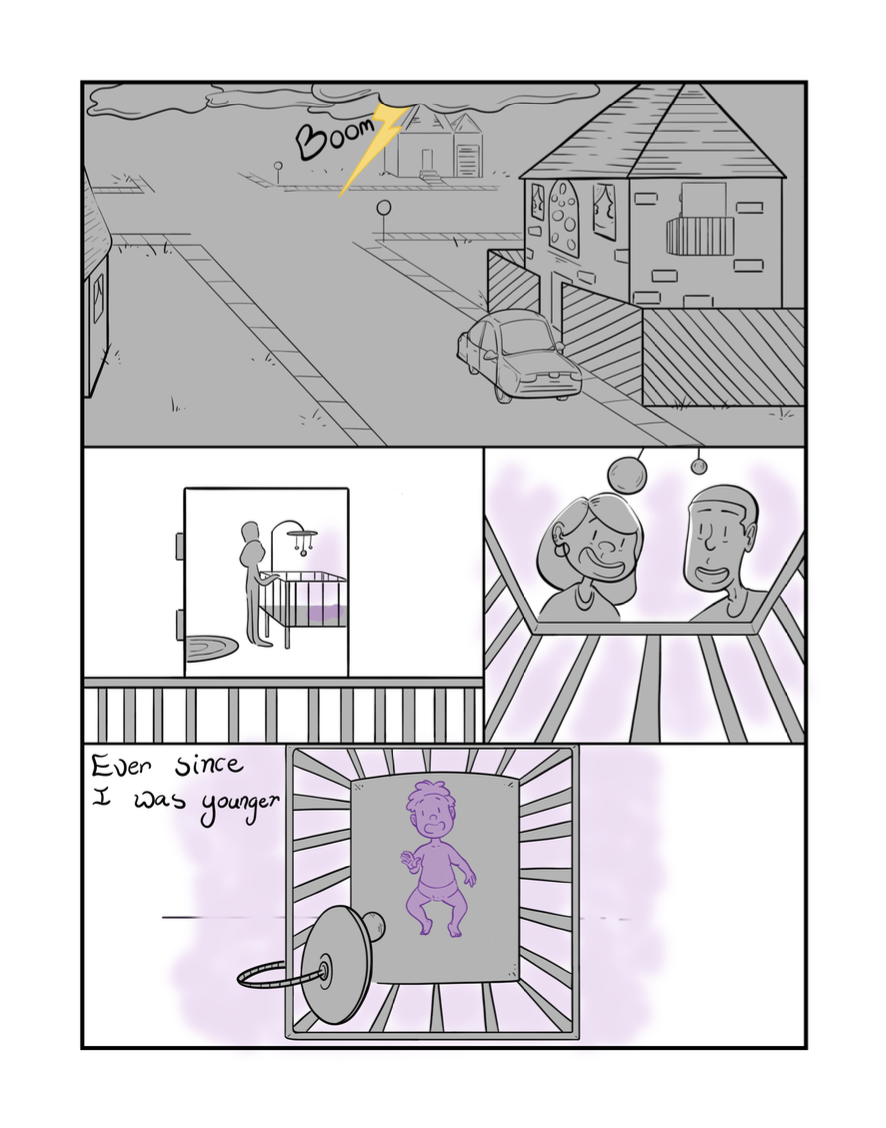

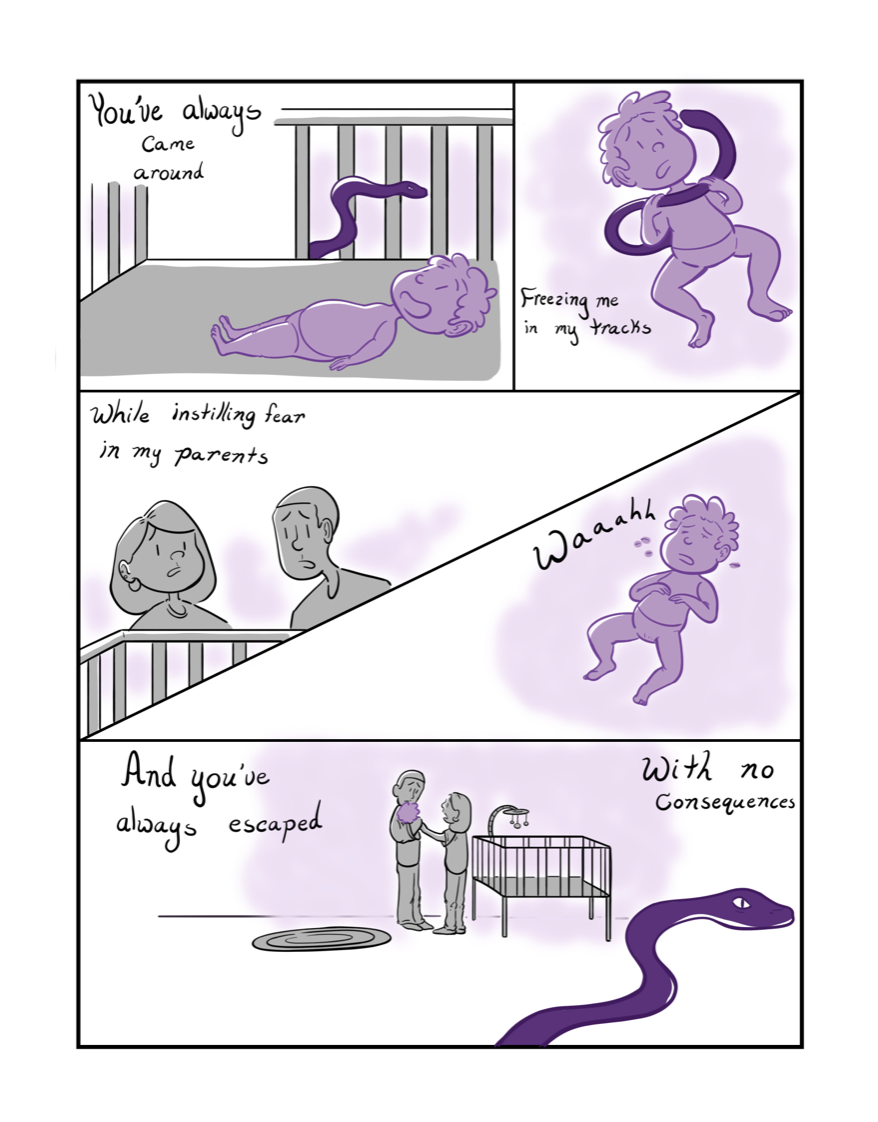

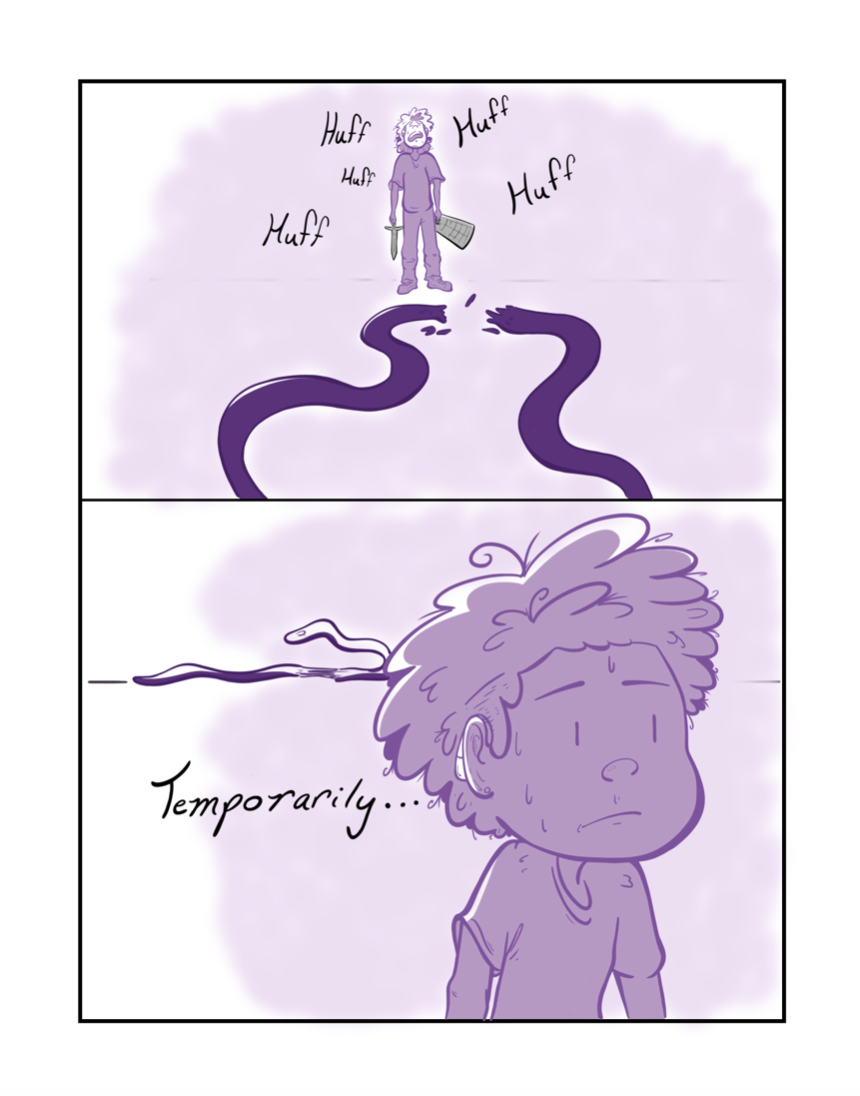

Memoir to Epilepsy (2022)

The piece is my experience with Epilepsy and finding a treatment that helps keep it at bay. I'm currently in my fourth year (senior year yay!). I'm a student at STAMPS.

Page 1: Top panel is completely grey with a yellow lightning strike. Written next to the lightning strike is the word “BOOM.” There is a faint outline of the neighborhood yet a detailed drawing on the right of a house with a car on the street and fence around it. The panel below on the left looks in through the patio. Two grey figures, Peninnah's parents, stand over a baby crib. The panel to the right looks from the point of view of the baby up at the two figures who are smiling. The bottom panel looks down on the purple baby in the crib from the two figures point of view.

Page 2: The panel on the left looks through the bars around the crib at the baby as a snake approaches. There is a lavender hue around the snake. The panel to the right shows the snake coiled around the baby's neck, the lavender hue surrounds them. In the panel below in the top left corner the parents look concerned looking down at the crib as the lavender hue rises. In the bottom right corner the baby cries surrounded by the lavender hue. The bottom panel shows her parents holding the baby surrounded by the lavender hue. The snake is in the foreground heading right.

Page 3: The top panel shows a young Peninnah, colored purple, surrounded by a lavender hue dropped down on one knee as the snake slivers around her. A grey ball is in front of her on the left. The middle panel shows the snake fully around Peninnah. Her art materials are spilled out on the floor to the right of her. The lavender hue surrounds Peninnah and the snake. The bottom panel shows the snake circled around Peninnah as she lies on the floor. The lavender hue still surrounds her. Her phone is tossed out to the right of her.

Page 4: The Greek symbol for time in purple borders the top and bottom of the page. The entire page is entirely lavender. Peninnah lies on the floor surrounded by a giant snake also in the form of the Greek symbol for time.

Page 5: The top panel shows two purple hands holding a sheet of paper that reads SCN1A surrounded by a lavender hue. The middle panel shows two grey figures, doctors, holding papers and sample tubes. The snake sits center on the panel in a cage all surrounded by a lavender hue. The bottom panel shows Peninnah being presented with a sword and shield surrounded by a lavender hue.

Page 6: The top panel shows Peninnah on the right side approaching a giant purple snake. She holds the sword and shield. Both characters are surrounded by the lavender hue. The bottom panel shows Peninnah slicing the head off of the giant snake surrounded by the lavender hue.

Page 7: The top panel shows Peninnah exhausted with words HUFF to show that she is breathing heavily. The snake body is sliced in half and is surrounded by a lavender hue. The bottom panel shows Peninnah leaving the the scene beads of sweat are on her face. The snake re-assembles in the background. Both characters are surrounded by a lavender hue.

About the Creator

Image description: Peninnah (she/her) is a black woman with curly hair. She wears a navy blue button up shirt with pink flowers. She is smiling at the camera from a 3/4ths angle.

The Dissection

I try not to talk to people about being in pain. There is no greater downer in a conversation than telling someone you’re in pain. People are kind; they want to help. When I tell them I’m in pain, they look sad; they ask what they can do. I don’t know how to say that I’ve already tried so many things. That I’ve seen a hundred doctors. That the specialist I finally got an appointment with doesn’t take insurance, so I pay $500 just to talk to him for an hour. That alternative medicine doesn’t have the answer – that I’ve tried exercise and yoga and magnesium and teas and extracts. That I understand why so many people are willing to do anything to cure themselves - like drink diluted bleach or wear copper socks or pray. I’m not religious, but sometimes I pray, just to see if some miracle might happen.

On the worst nights, I want to cut my legs off. It is lucky I have my husband to stop me from following through with such bad ideas. I am on a new medication that numbs the pain, but it numbs everything. I feel like a zombie. I tell my friends “I’m so, so tired. I sleep twelve hours a day.” They laugh and exclaim how hard this year of medical school has been. I don’t tell them that I don’t even know how hard the block has been because I am barely conscious during the lectures. At least I don’t spend the whole class googling cures and reading clinical case studies that I’ve already read. At least I don’t shake my legs so hard that the people next to me can’t focus.

One time I was given a gift card for a professional massage. It was an hour long and I told the massage therapist to only work on my legs. I asked for harder pressure five times before I could even feel it over the pain. Afterwards, I felt so relaxed. My legs were completely quiet for the entire ten-minute walk home. I lay down in the grass and looked at the sky for what felt like the first time in years. But then the feeling came creeping back. For a moment I had almost believed it was gone for good. I cried because I now knew what I was missing.

In anatomy class, we dissected the spine of our donor. She had so much hardware in her back – sixteen studs running down in parallel tracks. I think that she must have been in a lot of pain. When we use the chisel to break through her vertebrae, I think about how nice it must be to feel nothing. I scold myself for that dark line of thought. I can see her nerves, spreading out from the column. How can such a small line of tissue cause so much pain? When I’m done looking, I tuck the donor in gently as I would a friend. I hope she is resting easy, painless.

About the Author

Sophie Maloney

I am a first year medical student from rural upstate New York, where I grew up on a horse farm. I received an undergrad degree in math from Dartmouth and then worked in software development. I am interested in topology, ontology, and rural medicine. In my free time I like to hike and bike.

A Discarded People (2021)

Image Description: The installation sits on a grid created with charcoal. Divided in two, figures sit on the floor and are hung above in the grid on the wall. All figures are made from found trash. The figures pinned on the wall resemble legs, made out of various materials like twigs, wrappers, and glass. The figures on the ground resemble torsos, made out of materials like leaves, bottle caps, and pencils. The torsos reach and climb towards the grid and the legs.

The torsos below crawl and climb to reach the legs above. All they want is to become whole again. This piece is about that struggle to be functional, normal, whole. Even when doing so is detrimental to yourself. The grid represents society systematically not addressing issues of accessibility for those in need. I use trash both to comment on the fragility associated with disability, but to also elevate the materials along with my community. We are a discarded people.

About the Creator

Charlie Reynolds ( he/ him) is a conceptual artist who explores themes of war, gender, and disability using fibers, installations, and sculpture. During his time at the University of Michigan, Charlie hopes to expand his practice with a specific interest in weaving, hand dyeing, and quilting.

Image description: Charlie is a young white man with short brown hair. He is wearing glasses and a white shirt with colorful stripes. He is looking at the camera with trees in the background.

VangMD

Check your symptoms - Find a Doctor - Find an Optometrist - News - Contact Us - About

Home → Eye Health → Retinitis Pigmentosa → FAQ

Medically reviewed on: September 12, 2000

Last updated on: March 20, 2024

Retinitis Pigmentosa FAQ

Q: What is Retinitis Pigmentosa?

A: Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) is a rare, genetic degenerative eye disease. RP affects the retina, the light-sensitive layer of tissue found within the back of the eye– the vital mechanism allowing images to be sent to your brain. The disease causes the cells in the retina to break down slowly over time, causing vision loss. While varying between individuals, symptoms include decreased vision at night or in low light, blurred vision, sensitivity to bright light, and loss of colored vision.

Q: Who gets Retinitis Pigmentosa?

A: Your mother. Probably not your sisters. Maybe your future daughter.

Q: How can I catch Retinitis Pigmentosa?

A: Retinitis Pigmentosa is not contagious. You cannot “catch” Retinitis Pigmentosa. However, as your mother’s vision becomes worse, you will probably experience many of the same symptoms as she does, specifically: burnout, loss of appetite, fatigue, loneliness, and

depression.

Q: What are the symptoms of Retinitis Pigmentosa?

A: Initial symptoms include loss of night vision and gradual blind spots, both of which may be apparent in childhood. Later, the individual may experience complete blurriness of vision, clinical depression, fits of anger, the inability to drive, difficulty in social situations, increased anxiety, unemployment, trouble helping you with your math homework, and loss of ability to see her children’s beautiful faces.

Q: What causes Retinitis Pigmentosa?

A: Little is still known about Retinitis Pigmentosa. Doctors explain that the disease is caused by genetic mutations passed down from parent to child. In some cases, it can even occur sporadically. The cause of RP is especially difficult to specify as single mutations in over 60 different genes can trigger the disease. In your case, there’s a 25-50% chance for it to be passed along to you. This makes you wonder if Retinitis Pigmentosa will develop in your eyes someday.

Q: What can I expect after the diagnosis?

A: It depends. At first, things stay relatively the same. A little bit of extra help around the house is all she needs. You know that your mother is vision-impaired early in your childhood but it doesn’t completely register until she begins using a magnifying glass to read, increasing in power each year. “Your mother hasn’t completely lost her vision yet!” she exclaims. She still cooks the rice porridge she knows you and your siblings love. She still works all day on her feet at your aunt's restaurant, sweating and providing. She still pays the bills on time, even when the text becomes blurrier and blurrier. As you grow older, you and your siblings begin to understand the extent of your mother’s situation; quick on your feet to grab her a cup of tea or guide her to her favorite chair.

Q: Can Retinitis Pigmentosa be treated?

A: There is no treatment for Retinitis Pigmentosa. Some operations and medications can slow the progression of the disease but it’s inevitable. It makes you appreciate what your mother has done and continues to do for you. You begin to cry as you type this essay.

Q: Is there hope for a cure?

A: Always… in your heart at least. You hope that maybe one day her vision will spontaneously restore itself. You hope with each eye exam and new pair of glasses, somehow it will improve. You hope the prescribed eye drops will wash away her blurred vision like soap. But with today’s medicine, it’ll never come. Your mother has accepted this fact over many years but she does not feel guilty. Her cure lies within her children– finding purpose in their laughter and well-being. As you watch your mother find her way softly around the house, each step with investigation and purpose, you hope you can be half as strong as her when you grow up.

Q: What supports are in place for patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa?

A: Your grandma. Your aunt. You. Your siblings. All of the kind people who attend the church next to your house. We wouldn’t have made it this far without them. When you were younger, you couldn’t understand her situation. When your mother needed help, your grandma was always there. Then, as you grow up, something clicks. It clicks as your older brother becomes the man of the house. It clicks as that role is eventually passed on to you. The responsibilities fall directly into your hands. You get jobs as soon as legally possible– lessening the load on your mother. You learn to mature quickly, learn how to do things by yourself. You take school more seriously, striving towards every opportunity and scholarship you can get your hands on. When you get your driver’s license at age sixteen, you take on more. Your 1999 Honda Accord racking up miles as you become the family’s designated driver. When your mother’s field of vision becomes gradually less and less, you learn how to cook for yourself– making rice porridge like your mother used to, but never quite finding that exact taste like hers. Now, the responsibilities are handed down like an heirloom as your younger siblings come of age, and as you go to college.

Q: Will there be regrets as someone develops Retinitis Pigmentosa?

A: Yes, too many to count. You will regret all of the times you cried like a spoiled brat when you wanted a new toy. You will regret all of the times it worked. You will regret not doing your chores, and will regret it even more when seeing your mother do them after a long day at work. You will regret being a bad child and you will regret all of the headaches you’ve caused because of it. You will regret fighting with your siblings. You will regret all of the times you asked for expensive shoes, clothes, and electronics. You will regret ever complaining about it. You will regret raising your voice and feelings of frustration towards her. You will regret all of the times you forgot to take it back. You will regret missed opportunities and you will regret the time spent slacking off in school. You will regret the fact that she will never experience the same world as you, and you will regret ever taking her eyesight for granted.

Q: Will my mother go completely blind?

A: God, you hope not.

About the Author

Hi, My name is Brandon Vang (he/him), I am a 4th year here at UM studying Earth and Environmental Sciences. I am from Traverse City, Michigan and am interested in the fields of Ecology and Oceanography research amongst other things such as the Arts! I hope you enjoy my work!

Image description: Brandon is a young Asian man with short black hair. He is wearing glasses and a black sweater. He holds a rested face with focused eyes at the camera, behind a white backdrop.

When Health Can Hide

Before:

I got in,

But this wasn’t the plan.

Doesn’t matter, I was a fan.

Face lit up fast, no more wanting to be that absent girl.

But did I really want to go?

Could I leave the only hospitals I know?

Frightened by freedom.

I could be free from the same sterile offices and scheduled appointments and scans.

My own future at hand.

Maybe the pain would flee. Or I could flee from it.

If I moved far away, nobody would know what I had been through.

Nobody could tell me to stop trying to be someone new.

First weeks:

Smile and laugh, hide the liquid IV.

When offered to go out, simply agree.

Oh, and keep my medications in the closet.

And so classes began.

I remained a committed student, focusing only on what could be controlled.

You’re fine I’d be told.

If only they knew what I had been through.

I wrote part of my Common App with a hospital view.

And here I am now.

My symptoms are just an inconvenience...

Or the part of me that's laughed about.

It’s okay, sometimes I laugh too.

Except, when I laugh there's a different intention.

It’s joy that I earned this opportunity,

An opportunity for redemption.

Here now:

But, what am I here to redeem?

Is there something I need to prove?

I still don’t know.

I got in, and I want to stay.

To find people who understand.

To advocate on behalf of those like me.

Here I am now, sleep deprived,

Keeping my symptoms well-disguised.

But, I’m no more that absent girl.

Met with my professors.

Well what did they say?

Sounds good, just don’t miss your final essay.

Sure, I’ll try.

As if I can control the heart racing.

As if I can decide what I find myself facing.

Am I truly living...

Or just surviving the day?

It’s clear my symptoms are here to stay.

I wish:

I speak up again, for my needs are unmet.

If only I could simply forget.

Day and night I question.

A campus without barriers or doubts.

One that is completely accessible.

A dream.

The abilities I possessed before have been lost,

My hope for the future has only been tossed.

Here I am, living several states away from home.

I want to be seen.

Not only me, but you too.

If only we could just share what we’ve been through.

Hail:

A chronic illness, disability, and neurodivergent community.

Reflecting on systematic changes that need to be made.

Around campus our advocacy efforts are displayed.

No longer that absent girl,

But a worthy student who is building off her struggles, determination, and hope.

Looking for others to help me cope.

My education here is just at the start,

And I will make a difference,

One that feels right in my heart.

About the Author

Ashlyn Perry (she/her)

I am a first-year undergraduate student from the suburbs of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. I am studying Movement Science in the School of Kinesiology where I am also a Research Assistant. I have a strong interest in disability studies and advocacy, along with public health and public policy. Outside of academics I enjoy volunteering as a peer-buddy with the Best Buddies Program, serving in the Ann Arbor community with the Michigan Community Scholars Program (MCSP), and contributing to several other organizations here on the U-M campus.

Image description: Ashlyn is a young white woman with long brown hair. She is wearing a black sweater and a small gold necklace. She is standing in front of glass windows and smiling at the camera.

A Comfortable Prison (2022)

Image description: A white woman with short, brown hair, is shown lying in bed, her head on a colorful pillow. She is wearing an orange jumpsuit, akin to the ones worn in prison. There is a plain white shirt layered underneath. She has green eyes, with prominent eye bags, and a flushed face. There is a gloomy expression on her face as she looks to the left. We can see a patterned blanket, and on the textured blue green wall, there are drawn tally marks, 18.

“I want to stay in bed all day like she does, she’s so lucky.”

This is something I heard frequently in high school, when I first became disabled, and I still hear my peers whisper it around now that I'm in college. Out of frustration and exhaustion, I made this self portrait. My disability makes me feel imprisoned in my own body, I have so little control over any of it. I lose count of how many hours pass when I can't leave my bed, or what time of day it is. Being tired is not fatigue, being sore is not excruciating pain, and being glued to a bed for over 12 hours is definitely not lucky.

About the Creator

Grace Sirman

My name is Grace (she/her), and I'm a junior studying at the Stamps School of Art and Design. I'm a Mexican girl from Texas who loves to incorporate both my Mexican and my disabled identities in my artwork. I primarily illustrate digitally, but still create traditional work with colored pencils and gouache. I hope to become a visual development artist post graduation.

Image description: Grace is a young white woman with short brown hair, bleached eyebrows, and green eyes. She is wearing makeup, and is wearing a pink dress, only the straps are visible. She is smiling slightly at the camera.

Inclusion Reinterpreted

I arrive at my building on campus. The poster on the double doors says "Masks Required." It has been there since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is now September of 2021, the beginning of my 7th year as a Ph.D. student and a year and a half into the pandemic. A few weeks ago, the COVID numbers in the US were the lowest they've been, only 223.4 deaths per day (1,2). But with the start of school and the new Delta variant, cases are rising again. So as of August, the University has reinstated mandatory masking in all campus buildings (3).

I walk to my office. The halls along the way are filled with bulletin boards covered in glossy posters of smiling students and words like "Respect," and "Diversity," and "Inclusion." When I reach my office, I toss my coat over the back of my chair. It's a small room with four desks spanning the walls, two on each side, and enough room to walk between them, if you turn sideways. I pick up a webcam and go to the room where I teach. The school's deans have declared that all classes must be taught in person. But we are allowed to teach hybrid, if we want. I set up the webcam, load up my slides, and look over a list of questions I've gotten this week. When class starts, I am the only one in the room. There are about 20 students on zoom. They prefer it. I prefer it too, but the school has officially returned to in-person instruction, so I need to be there. I teach.

An hour and a half later, I pack up and head back to my office. I am making preparations for the experiment that will complete my dissertation and I have a lot to do. When I get back to my office, one of my five officemates is sitting at the desk next to mine. They are not wearing a mask. I say "good morning" and make eye contact, my mask clearly visible. I sit at my desk and start organizing my work for the day. My officemate goes back to their work, still unmasked.

I think about the effects getting COVID would have on me and my loved ones.

I think about my major depressive disorder. I've learned, through many years of painful trial and error, that I need at least 30 minutes of daily exercise to reliably prevent a months-long depressive episode. I think about how those episodes make it nearly impossible to focus, or concentrate, or even to get out of bed. A depressive episode means I can't work. I can't teach. I can't take care of my family, or even take care of myself. I've worked so incredibly hard to build the exercise and sleep I need into my routine, and to stick to it, so I can continue to function. But even a small cold can disrupt that routine and put me at risk. Getting COVID would almost certainly trigger a depressive episode that would take many painful weeks or months to recover from, assuming I remain one of the lucky ones that comes out alive.

I think about my partner who lives in constant pain from a chronic illness. On good days, their pain is distracting. On bad days it's excruciating and leaves them bedridden. They work hard to balance work, parenting, and living life. They do their best to fit all those into their limited good days. COVID could mean no good days for weeks, and Long COVID could mean even fewer good days for the rest of their life. They could lose their job, their health insurance, their hobbies, and their ability to parent. They have to work so hard already, they don't deserve to have any more of their life stolen from them.

I think about my elderly father who I take care of. He never finished high school, but he worked ten hours a day, six days a week to put me through undergrad. He has emphysema, and at his age, he very well might not survive COVID. If I got it on campus and then gave it to him, I couldn't forgive myself.

But most of all, I think about my five year old daughter. I think about her brave smile after her second open-heart surgery. That was when she was two. The doctors gave her a 95% chance to survive that surgery. She's going to need another one before she's an adult. She takes medication every day to keep her heart healthy. Her condition puts her at higher risk for the cardiovascular complications of COVID (4), and getting COVID could interfere with her next surgery. I need to do everything I can to keep her heart in good condition for that next surgery.

I look at my unmasked officemate.

"Do you need a mask?" I ask.

"I think we don't need to do that anymore," they reply.

"Pretty sure we do," I say.

I'm not surprised. I've had this same conversation dozens of times. When the University reinstated mandatory masking, my school didn't announce the policy. Instead, there was one mention, as an aside, in an email about room reservations, suggesting masking in shared spaces. The only reason I know is from seeing an article in the news and searching the University website for the current policy. Since then, I've been told confidently by my peers and professors that masks aren't required anymore. Or that masks are only required in classrooms. Or if you have symptoms. Or only if the door is open. Or if the door is closed. None of the students or faculty I've talked to know there is a written policy. My peers didn't get the memo, because there was no memo.

My officemate starts digging through their bag looking for a mask. I think about the research showing that the virus stays viable in aerosol droplets for hours after someone exhales them (5). I think about the research showing that masks are better at stopping contagious people from spreading the virus than they are at protecting the wearer (5,6). If my officemate is infected, masking up now won't be much help. I pack up my work and go home.

I email the associate dean in charge of office policy, asking if he can make an announcement to clarify the policy on masking. He replies, noting that there is an exception for "single enclosed private offices" and says his interpretation is therefore that "it should be OK to remove the mask when alone in an office," even a shared office. The exception is clearly meant for offices with a single desk reserved for a single person, not for offices with four desks regularly shared by six students. That is not what "single enclosed private office" means in the English language. I think to myself that there is no way a tenured faculty member with a Ph.D. actually believes it does. I only imagine, for example, how a new professor promised a "private office" would react if they arrived to find four desks and five other professors sharing the space.

I email academic HR, explaining the office configuration used by grad students at our school, and ask if the associate dean is correct that there is an exception to the masking policy. They respond: "Your example is not among those listed as an exception to the indoor masking mandate." This seems clear enough, masking is in fact required in our offices. I email the associate dean again, forwarding my exchange with HR. He responds: "My official interpretation is that our offices are private at times when only one person is in them and not private when multiple people are in them." He says he will send out a survey so that students can decide whether or not masks will be required in their office.

I try to reason one more time. I respond, explaining that HR has already confirmed he is violating university policy. I say that the policy is meant to protect disabled people, and people with disabled family members. I say that knowingly violating that policy is discrimination, and that it puts my health and life at risk. He replies: "On the interpretation of the university policy, you and I will have to respectfully disagree." He knows he is violating University policy. He knows he is discriminating against disabled students. But he also knows no one will stop him, because he's a dean.

Days go by. I get an email saying I have been assigned to a new office, designated as mandatory masking. I go to campus to exchange my key and move my things. When I get to the new office, it is the same size as my old office. Four desks. But there are eight names on the nameplate by the door. It turns out that all of the students who wanted the University's masking policy enforced were assigned to the same office. On my way out that day, I pass several offices. In many of them, I see people sitting side-by-side, unmasked.

I have spent the past decade studying networks, the flow of things like traffic, and ideas—and diseases. I know that if a disease is allowed to spread through a partially vaccinated population, the likely result is new vaccine-resistant variants. I know that more people will die, and that a lot of them will be people like me and my family.

I contact the union and file a grievance. HR tells us they need time to research the issue. Weeks go by. Finally, I get an email. I read the email. I wish I could say the dean changed his mind and decided to follow the University policy. I wish I could say that HR insisted the dean follow university policy, or that Environmental Health and Safety stood up for their own policy, or that the other deans, or the provost, or the president stepped in to enforce the policy. I wish I could say that the University followed through on its promises to disabled students.

According to the email, the deans of my school have been talking to Environmental Health and Safety. The University will be revising the masking policy. "Single enclosed private office" is being changed to "alone in an enclosed office." When a dean breaks a rule, just change the rule.

I go on with my work. I start working from home whenever I can. The Omicron variant surges. On class days, I drive to campus and teach, often to a webcam in an empty classroom. After that, I leave. I walk past the offices of my unmasked peers and professors. I walk past the glossy posters that say "Respect," and "Diversity," and "Inclusion." Then I walk out through the double doors with the "Masks Required" poster, printed on the same thin glossy paper.

Works Cited

1 . Fagen-Ulmschneider W. 91-DIVOC. Retrieved March 18, 2024 from

https://91-divoc.com/pages/covid-visualization/?chart=countries&highlight=United%20States&show=highli

ght-only&y=fixed&scale=linear&data=deaths-daily-7&data-source=jhu&xaxis=right#countries

2. Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 Data

Repository. Retrieved March 18, 2024 from https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19

3. Jordan, D. (2021, August 9). "U-M to require face coverings indoors across all campuses." The

University Record. https://record.umich.edu/articles/u-m-to-require-face-coverings-indoors-across-all-campuses/

4. Farshidfar, F., Koleini, N., & Ardehali, H. (2021). Cardiovascular complications of COVID-19. JCI insight,

6(13).

5. Van Doremalen, N., Bushmaker, T., Morris, D. H., Holbrook, M. G., Gamble, A., Williamson, B. N., ... &

Munster, V. J. (2020). Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. New

England journal of medicine, 382(16), 1564-1567.

6. Lindsley, W. G., Beezhold, D. H., Coyle, J., Derk, R. C., Blachere, F. M., Boots, T., ... & Noti, J. D.

(2021). Efficacy of universal masking for source control and personal protection from simulated cough

and exhaled aerosols in a room. Journal of occupational and environmental hygiene, 18(8), 409-422.

7. Coyle, J. P., Derk, R. C., Lindsley, W. G., Blachere, F. M., Boots, T., Lemons, A. R., ... & Noti, J. D.

(2021). Efficacy of ventilation, HEPA air cleaners, universal masking, and physical distancing for reducing

exposure to simulated exhaled aerosols in a meeting room. Viruses, 13(12), 2536.

About the Author

Edward L. Platt, Ph.D.

Edward (he/they) completed his Ph.D. in Information Science in 2022. He lives in Ann Arbor with his partner, child, and cats. Since graduation, he has started a consultancy working with researchers and non-profits on cooperative governance and Free/Open-Source Software.

Image description: Edward is a middle-aged white man with short facial hair and long braids. He is wearing a scarf and striped sweater. He is sitting at a desk, smiling at the camera.

An MCAT Personal Statement

Dear MCAT accommodations committee,

You asked me a question, it went something like this;

“Write a personal statement why you feel it is necessary to ‘level the playing field’ on the MCAT exam.”

To write a defense of my disabilities.

After the high school achievements

The pre-med courses

The hours working in a hospital ER

The papers published

After doctors notes and IEP meetings

The 504s written, defended, and revised

The hours of testing and hospital stays

The families torn apart and siblings pushed to the side

It all comes down to this.

And you’re asking me why?

Not if, not how, but why?

Why should you care, and I have to come up with the reason

To prove to you in 500 words what has taken my life

Perhaps,

Instead,

You might prefer,

A jar of the tears my mother cried when her first born couldn’t stand her touch My father’s orange bottles, emptied of the sleeping pills he took when I kept him up at night The fly ball my parents never saw my brother catch The missing birthday gifts when my treatments cost too much

Would that prove my plight to you?

In exchange for extending time?

About the Author

Eva Goren (she/they)

I am a third year undergraduate student at the University of Michigan's LSA school pursuing Biopsychology and the Middle East. I hope to attend medical school after completing my B.S. In my free time I enjoy listening to podcasts, cooking with friends, and water coloring with my roommate.

Narcolepsy

Near, drawing ever closer, the promise of rest

Always beckoning, Morpheus (1) cries out to my soul

Relentlessly, Slumber pulls at me, dragging me down

Crushing is the weight of exhaustion upon my brow

Overpowered; my freedom, my thought, my energy, fade

Lashed to the mast, Somnus’ (2) siren song (3) calls, yet I never reach

Every breath takes me closer to a land of respite

Promises of rest, a sweet place, in this land, a time to heal

Sleep, my cruel mistress, bars the gates to my visit

Yet, I am trapped, far from repose; I dream of sleep

1: Morpheus - Greek god of dreams

2: Somnus - Roman god of sleep

3: Lashed to the mast (...) siren song - Reference to Homer’s Odyssey, where Odysseus lashes himself to the mast of his ship as they pass the Island of the Sirens so that he may hear their song and hear the true desires of his heart without steering the ship into danger. This poem seeks to elicit similar imagery of hearing the call to sleep but not being able to reach Somnus, who serves as the personification of sleep here.

Author’s Note on the work:

This piece explores the experience of sleep for a person living with narcolepsy. There is a deliberate focus on creating a repetitive theme through the personification of sleep and how, for those with narcolepsy, sleep is a cruel duality. Sleep promises rest, but it never delivers. Ultimately, the poem, as well as what life can be like for those with narcolepsy, is emphasized in the final line: a state of being trapped between being awake and asleep.

Author’s Note on Narcolepsy:

As a student and a nursing professional living with narcolepsy, the chronic fatigue related to this disorder can make daily life a challenge. Personally, I am extremely grateful that I have greater control of my condition through medications. This requires that I often take medications to keep myself awake and medication to ensure my body sleeps. Living with narcolepsy has given me a deep understanding of what it means to be exhausted. Life as a student is never easy, and adding chronic fatigue to everyday life creates a significant challenge. In many ways, narcolepsy is an invisible disorder, similar to other conditions causing chronic fatigue. Through creating this emotionally charged poem, I hope readers can share the experience of narcolepsy and those living with chronic fatigue.

About the Author

Thomas (Tom) Richey (he/him) is a Doctorate of Family Nursing Practice candidate at the University of Michigan, with a tentative graduate date of May 2025. Tom is passionate about providing healthcare services to underserved and marginalized populations. As a National Health Services Corps Scholar, Tom is seeking to dedicate his life to empowering the communities in which he will have the privilege of serving as a primary care provider.

Big

My implant battery beeps orange! It didn’t charge through the night.

I roll out of bed, take off my pajamas and detach my insulin pump. I throw it onto the bed and quickly pull on jeans — leaving them unzipped so I can reattach my pump and tuck it into a pocket. I rummage in my room for my backup cochlear implant battery. Once found, I secure it onto my implant and place it around my left ear. I hook my hearing aid onto my right ear. Now I can hear Dad rustling in the kitchen as my phone plays, “Lucky I’m still sane after all I’ve been through...” I sing along to Joe Walsh. I pack extra hearing aid batteries in my backpack so I don't go deaf at school. He hands me lunch as I rush to the front door.

“Love you, I’ll see you after school,” I say to him.

“Is your pump charged?” Mom asks. I roll my eyes and shrug a yes without actually checking.

“Do you have carbs?” questions Dad.

Obviously I have carbs, you just handed me lunch, I think to myself. I say yes as I walk out the door.

“Call if you need anything!” Mom says as the door closes.

Pulling out of the driveway, I hear, “beep beep buzz”. It’s my pump, which buzzes when it is down to a 5% charge.

“UGHHH,” Of course. I should have checked my pump to see it was charged I think as I run back into the house and grab a USB charger. Back in the car, charging my almost dead pump, I do a mental checklist:

Pump, check.

Charge, check.

Carbs, check.

Insulin... I look at my pump to double-check... insulin, check.

Dex (Continuous Glucose Monitor) check.

Hearing aid, check.

Implant, check.

Extra batteries, check.

Phone, of course.

Every. Single. Day. This is me getting out the front door.

This is my life as a ‘normal’ teenager living with diabetes and 97% deafness. It’s not as black and white as I paint it; it’s actually much more challenging. Some days my CGM stops working and calls start rolling in from Mom and Dad asking for my blood glucose number. Or, I run out of insulin, or worst-case scenario, I don't have carbs and pass out.

Some days are better than others. But there are also days when I wonder why? At school, I’ve become the butt of the joke being the deaf kid. I find it easier to laugh it off rather than stand up for myself.

“Helen Keller,” they laugh.

Are you too clueless to realize that's offensive? I think while I struggle to smile.

I find myself saying “what” for the third time, having no idea what the people around me are saying. “HAHA, imagine being deaf.”

Ouch.

It’s not like it’s my fault. I was born like this, and I chose to participate in life. I spent years training with an Auditory Verbal Therapist, years perfecting the sound on my hearing aids with an audiologist, just to be ignored by my peers. It’s practically the same for my diabetes. “Aren't you diabetic?” they ask, “You probably shouldn’t be eating that.”

You have no idea what I should and shouldn't be eating.

”Actually, I have an insulin pump which gives a bolus of insulin when I eat something,” I respond.

“Aren’t diabetics supposed to be fat?”

AGGGHHH, I scream internally.

I’ve been asked before, “If there was a cure, would you take it?”

I ponder this question. I think I wouldn’t trade the experiences I've encountered from being deaf and diabetic for anything. I have an amazing family and support group. I have accepted that sometimes everything is not going to be perfect. I’ve accomplished a lot already and there’s so much more out there for me to do.

So I respond, “No, because this is who I am.”

About the Author

Lulu Hirschfield

Hi all! I am a second year student here at the University of Michigan. I grew up in sunny San Diego, California and decided to come to U of M to pursue my dreams of being a D1 athlete where I compete here on the women's varsity water polo team. Currently studying Exercise Science, and thoroughly enjoying it, I am still unsure what my aspirations are for the future. As for right now I'm just trying to learn as much as possible and one day be back in California to surf!

Scatterbrain (2023)

Image description: A person's figure is shown from the shoulders up, only they have been stripped of their skin so only bone and muscle mass remain. Their mouth is slightly parted in anxiety as inside their brain shows a pixelated recreation of the 2001 Microsoft Windows desktop background. Several brightly colored error messages and pop-up tabs surround the dull figure. One of the figure's eyes is turned directly towards the viewer.